6/17/2019

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies bind to bacteria in the gut, and, according to the study, the more bacteria that’s tied up with IgA, the less likely babies are to develop NEC. Since preterm infants get IgA only from mothers’ milk in their fragile first weeks of life, the authors emphasize the importance of breastmilk for these babies. The study appears today in

Nature Medicine.

“It’s been well known for a decade that babies who get NEC have particular bacteria—Enterobacteriaceae—in their guts, but what we found is that it’s not how much Enterobacteriaceae there is, but whether it’s bound to IgA that matters. And that’s potentially actionable,” said senior author Timothy Hand, Ph.D., assistant professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the

R.K. Mellon Institute for Pediatric Research and

Pitt’s School of Medicine.

The researchers looked at fecal samples from 30 preterm infants with NEC and 39 age-matched controls. Overall, breastmilk-fed babies had more IgA-bound gut bacteria than their formula-fed peers, and those who developed NEC were more likely to have been formula-fed.

Tracking these infants’ gut microbiomes over time, Hand’s team found that for the healthy babies, Enterobacteriaceae was largely tied up by IgA, allowing diverse bacterial flora to flourish. But for the NEC infants in the days leading up to diagnosis, IgA-unbound Enterobacteriaceae was free to take over.

To demonstrate causation between IgA and NEC, Hand and his team used a mouse model.

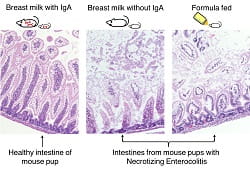

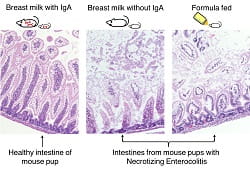

The researchers bred mice that couldn’t produce IgA in their breastmilk. Pups reared on IgA-free milk were just as susceptible to NEC as their formula-fed littermates. So, breastfeeding in and of itself is not sufficient for NEC prevention. The milk must contain IgA to confer this specific benefit.

But the solution for NEC may not be as simple as putting IgA into formula, Hand said. Because breastmilk has other benefits beyond IgA, donor milk is still the best option to fill the gap when breastfeeding or providing pumped maternal milk isn’t an option.

“What we showed is that IgA is necessary but may not be sufficient to prevent NEC,” Hand said. “What we’re arguing is that you might want to test the antibody content of donor milk and then target the most protective milk to the most at-risk infants.”

Other authors on the study include Benjamin Macadangdang, M.D., Ph.D., Justin Tometich, Robyn Baker, Junyi Ji, Ansen Burr and Congrong Ma, M.S., from UPMC Children’s Hospital; Matthew Rogers, Ph.D., Brian Firek, M.S., and Michael Morowitz, M.S., from Pitt; and Misty Good, M.D., from

Washington University School of Medicine.

PHOTO INFO: (click images for high-res versions)

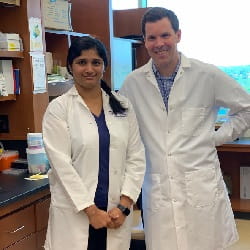

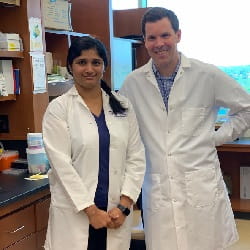

TOP:

CREDIT: Dr. Timothy Hand

CAPTION: First author Kathyayini Gopalakrishna, M.D., poses with her advisor, senior author Timothy Hand, Ph.D.

BOTTOM:

CREDIT: Dr. Kathyayini Gopalakrishna

CAPTION: Mice reared by IgA-deficient mothers were just as susceptible to NEC as formula-fed mice.

“It’s been well known for a decade that babies who get NEC have particular bacteria—Enterobacteriaceae—in their guts, but what we found is that it’s not how much Enterobacteriaceae there is, but whether it’s bound to IgA that matters. And that’s potentially actionable,” said senior author Timothy Hand, Ph.D., assistant professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the R.K. Mellon Institute for Pediatric Research and Pitt’s School of Medicine.

“It’s been well known for a decade that babies who get NEC have particular bacteria—Enterobacteriaceae—in their guts, but what we found is that it’s not how much Enterobacteriaceae there is, but whether it’s bound to IgA that matters. And that’s potentially actionable,” said senior author Timothy Hand, Ph.D., assistant professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the R.K. Mellon Institute for Pediatric Research and Pitt’s School of Medicine. The researchers bred mice that couldn’t produce IgA in their breastmilk. Pups reared on IgA-free milk were just as susceptible to NEC as their formula-fed littermates. So, breastfeeding in and of itself is not sufficient for NEC prevention. The milk must contain IgA to confer this specific benefit.

The researchers bred mice that couldn’t produce IgA in their breastmilk. Pups reared on IgA-free milk were just as susceptible to NEC as their formula-fed littermates. So, breastfeeding in and of itself is not sufficient for NEC prevention. The milk must contain IgA to confer this specific benefit.