7/17/2019

PITTSBURGH – Aging research indicates that better healthspan—the quality of life as we age—may be more important than lifespan.

In a report published today in Nature Communications, a surprising new genetic discovery by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh suggests that there may be molecular switches that control lifespan and healthspan separately.

Healthspan is represented by a set of parameters like mobility and immune resistance that are distinct from lifespan, which can be easily measured. Though it is harder to study, in the long run, it may be more relevant to modify healthspan, notes senior author Arjumand Ghazi, Ph.D., associate professor of pediatrics, developmental biology and cell biology, Pitt School of Medicine and UPMC Children’s Hospital, recalling the Greek myth of Eos and Tithonus to describe the difference. “The goddess Eos fell in love with a mortal man, Tithonus, and asked that he be granted eternal life, but forgot to ask for eternal youth. Tithonus lived forever but as a frail and immobile old man.”

In the current study, Ghazi and her team focused on a protein called TCER-1 in the worm Caenorhabditis elegans. Earlier work from their lab showed that TCER-1 promotes longevity in worms and also is critical to its fertility.

In the current study, Ghazi and her team focused on a protein called TCER-1 in the worm Caenorhabditis elegans. Earlier work from their lab showed that TCER-1 promotes longevity in worms and also is critical to its fertility.

Longevity genes in many animals increase resistance to stressors, such as infection, so the researchers expected that removing TCER-1 would make the worms less resilient.

Longevity genes in many animals increase resistance to stressors, such as infection, so the researchers expected that removing TCER-1 would make the worms less resilient.

Much to their surprise, they saw the exact opposite. When infected with bacteria, subjected to DNA-damaging radiation or high temperatures, worms without TCER-1 survived much longer than normal worms. They also had improved mobility with age and were less prone to protein clumping that causes human neurodegenerative diseases. Conversely, increasing TCER-1 levels beyond normal suppressed the animal’s immune defenses.

“I was sure I’d made a mistake somewhere,” says Francis Amrit, Ph.D., the study’s lead author and a staff scientist in Ghazi’s lab. “But I repeated the experiments and realized that TCER-1 was unlike any other longevity gene we’d seen before—it was actually suppressing immune resistance.”

“I liken TCER-1 in C. elegans to a DJ who controls the base, treble and other tones to get the music to sound just right,” says Amrit. “During its reproductive age, TCER-1 tunes all the molecular dials to ensure that the animal reproduces efficiently to propagate the species, partly by diverting resources meant for stress management.”

Ghazi cautions that it is too soon to make any conclusions about human healthspan, but notes that the finding should change how we understand the molecular basis of aging.

“It will be interesting to understand how the body allocates resources,” Ghazi speculates. “For example, could women one day take a pill once they decide to stop having children that would improve their healthspan by diverting resources used for reproduction toward improved stress resilience?”

Additional study authors include Nikki Naim, Ramesh Ratnappan, Ph.D., Julia Loose, Carter Mason, Laura Steenberge, Brooke McClendon, Ph.D., and Judith L. Yanowitz, Ph.D., all of Pitt; and Guoqiang Wang, Ph.D., and Monica Driscoll, Ph.D., of Rutgers University.

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01AG051659 and by the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research.

IMAGE INFO: (click image for high-res version)

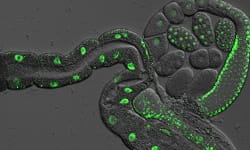

CREDIT: Francis Arjumand Ghazi/University of Pittsburgh

CAPTION: Gut and germ cells of a young adult worm showing green fluorescence where the protein TCER-1 is produced.

VIDEO INFO:

CREDIT: Arjumand Ghazi/University of Pittsburgh

CAPTION: Removing TCER-1 improves mobility in worms paralyzed by toxic buildup of amyloid beta protein.