It was around Thanksgiving 2020 when 15-year-old Butler, Pa. resident Luke Cunningham began having frequent and intense nosebleeds.

Luke says that he had also had trouble breathing out of one side of his nose for a while, but both he and his mother, Melissa, had chalked it up to an incident with his brother that had occurred a year earlier.

Luke says that he had also had trouble breathing out of one side of his nose for a while, but both he and his mother, Melissa, had chalked it up to an incident with his brother that had occurred a year earlier.

“We had thought his brother had broken his nose while wrestling one day,” says Melissa.

But the nosebleeds continued to grow worse and more frequent, sometimes resulting in Luke waking in the middle of the night gurgling on blood.

The Cunninghams made several trips to the local emergency room, but doctors there weren’t sure what exactly they were dealing with.

Melissa says they tried a cauterization, but that didn’t help. Eventually, it was recommended that the Cunninghams go to an ENT (Ear, Nose, and Throat doctor) in Butler for more answers.

The ENT doctor looked in [Luke’s] nose and thought that he knew what he was looking at, but he recommended that Luke and his family go to UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh for a diagnosis.

The ENT doctor looked in [Luke’s] nose and thought that he knew what he was looking at, but he recommended that Luke and his family go to UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh for a diagnosis.

Luke was able to get in that same day at UPMC Children’s, where doctors conducted an MRI and confirmed what the ENT doctor had suspected: Luke had a juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma tumor.

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas – or JNAs – are rare tumors made of blood vessels that grow in the sinuses and nasal cavity. While these growths are benign (non-cancerous), they are still serious. JNAs can bleed profusely, spread and damage nerves and bones, and block ear and sinus drainage.

“With JNAs, teenage boys can present with nasal obstruction or severe nosebleeds, like Luke did,” says Amanda Stapleton, MD, pediatric otolaryngologist and endoscopic sinus and skull base surgeon at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

How JNAs develop is not exactly known, but because these tumors occur almost exclusively in adolescent boys, hormones are thought to play a role.

“These tumors have to be removed surgically. The good news is that after a complete surgical resection, once an adolescent male finishes puberty, there is a low likelihood of recurrent growth of the tumor,” Dr. Stapleton says.

For Luke, the tumor had to be removed to un-obstruct his airway, stop the extreme nosebleeds, and prevent further risks.

Dr. Stapleton is part of a team of surgeons on Luke’s case. She began to assemble the multidisciplinary team she would need to conduct a successful surgery including Paul Gardner, MD, from Neurosurgery and a doctor from Pediatric Neurosurgery. Experts from Interventional Radiology were also a key part of the team, as they would be responsible for embolizing the large blood vessels that supply the tumor a day before the surgery to remove the tumor.

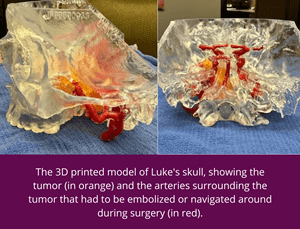

Because of the complicated nature of the surgery, Dr. Stapleton also had a 3D model of Luke’s tumor created so that she could both plan her surgical intervention and show the Cunninghams exactly what she would be doing.

Because of the complicated nature of the surgery, Dr. Stapleton also had a 3D model of Luke’s tumor created so that she could both plan her surgical intervention and show the Cunninghams exactly what she would be doing.

In January 2021, Luke underwent two days of surgical intervention to remove his tumor. The first surgical procedure occurred on a Friday when the interventional radiologist went in through an artery in Luke’s groin to embolize the tumor and stop the major blood source of the tumor.

The following Monday, Dr. Stapleton and her neurosurgery colleagues successfully resected Luke’s tumor via an endoscopic surgery through the nose. He spent one night in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. By that Wednesday, Luke was released from the hospital.

The following Monday, Dr. Stapleton and her neurosurgery colleagues successfully resected Luke’s tumor via an endoscopic surgery through the nose. He spent one night in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. By that Wednesday, Luke was released from the hospital.

Luke had to undergo routine imaging every three months and then every six months after surgery to ensure that they had successfully removed the entire tumor. Dr. Stapleton says that if they left any of the tumor behind it could grow back.

“Fortunately, his tumor was completely resected, and we have seen no evidence of regrowth on his routine follow-up imaging,” she says.

He is now almost two years out from his surgeries and going into his senior year of high school. He plays baseball, works part-time at a car dealership, and enjoys playing video games and working out. He has regained function of both of his airways and the nosebleeds have gone away. Going forward, he’ll stop at Children’s on a yearly basis to keep an eye on things.

“The whole thing was a very smooth process,” says Melissa. “Everything is so positive about Children’s. We never had a problem getting an appointment, never had issues, never had to wait to be seen. Even after his surgery, he was in the ICU for the night – which was normal, but definitely stressful. And everyone was fantastic.”

To make a referral to the UPMC Children’s Division of Otolaryngology (Ear, Nose, and Throat), please call 412-692-5460.