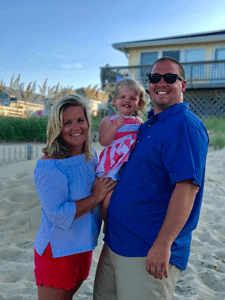

A few days after Laura and Jason Singer of Pittsburgh, Pa. (McCandless Township) had their first child, Reagan, they felt relieved. Everything seemed fine after a tough delivery.

A few days after Laura and Jason Singer of Pittsburgh, Pa. (McCandless Township) had their first child, Reagan, they felt relieved. Everything seemed fine after a tough delivery.

But their relief soon turned to concern when they got a call from their pediatrician.

The routine newborn screening at Magee-Womens Hospital of UPMC showed their daughter had tested positive for a rare inborn error of metabolism.

At three months, testing confirmed that Reagan had trifunctional protein (TFP) deficiency.

TFP deficiency prevents the body from turning fats into energy, mostly during times without food. In children with TFP deficiency, an enzyme that helps the body use stored fat for energy is missing or defective.

When the body can’t convert fat into energy, levels of fatty acids build up.

Left untreated, fatty acids can cause problems with the:

|

|

Children with TFP deficiency may have symptoms such as:

|

|

Leading TFP Deficiency Researchers Close to Home

“We had to Google the disorder, and it was scary,” says Laura.

“Our pediatrician referred us to a genetic specialist at Children’s Hospital, who wanted us to bring the baby in on a Sunday. When a specialist wants to see your child on a Sunday, you sort of panic,” says Laura.

But that Sunday visit with Jerry Vockley, MD, director of the Center for Rare Disease Therapy, calmed their fears.

“Dr. Vockley answered our every question and concern that day,” adds Jason. “We felt scared. But it was phenomenal to learn one of the top researchers on this condition was literally 20 minutes from our house.”

Planning a Special Diet for Reagan

The Singers’ first step was to work with a nutrition specialist to come up with an action plan.

When TFP is missing or not working right, the body can't use fats for energy. Instead, it must rely solely on a type of sugar called glucose.

When a child misses a meal — such as when they’re sleeping — or doesn’t eat for a while, glucose levels can dip. This leads to low blood sugar and the buildup of harmful substances in the blood.

To prevent a dip in glucose levels, kids with TFP deficiency must not go more than a few hours without eating carbohydrates.

When Reagan was an infant, Laura and Jason had to make sure they fed her every four hours. They used regular formula at first, then transitioned to a lower-fat, specialized blend formula with a carbohydrate supplement.

They would have to wake her up during the night for feedings, even though she had started sleeping longer through the nights.

As Reagan got older, she had to learn how to chew food because she'd been on a liquid diet for so long. And now that she's two, she can eat anything she likes, as long as her parents watch her calories and fat grams.

She can eat many foods, such as low-fat macaroni and cheese and the occasional French fry.

A Growing, Thriving Two-Year-Old

Despite her disease, Reagan has reached all her developmental milestones on schedule and is as active as any other two-year-old.

The key to keeping Reagan healthy is frequently checking her blood sugar levels — like a child with type 1 diabetes. This is especially vital if she should become sick because the body burns more energy when it's sick.

And, since it's often hard to get sick children to eat, colds or other minor illnesses can quickly become serious for Reagan.

She's been in the hospital three times, but Laura and Jason now know what to watch for.

“She becomes very lethargic, so we really have to step up our game to keep her eating when she’s sick,” says Jason.

Watching her closely will be important for the next few years until Reagan's old enough to communicate exactly how she's feeling.

The Singers take Reagan to see Dr. Vockley for checkups every three months. They have built strong bonds with the team who cares for Reagan.

“We receive personalized care that focuses on how Reagan is growing, not just on the disorder,” says Laura. “The team supports us and gives us reassurance. They always help us to feel hopeful about Reagan’s future.”

Although the family must continue Reagan’s low-fat diet and be extra cautious during illnesses that might cause infections, her prognosis is positive.

With proper treatment, doctors expect Reagan to continue normal growth and development.

Contact Us

At the Center for Rare Disease Therapy, every child diagnosed with a rare disease receives an individualized treatment plan and family-centered care.

For an appointment, consult, or referral, contact us:

- Phone at 412-692-7273.

- Email at rarecare@chp.edu.

- Fill out our rare disease contact form.

We’ll be in touch within 2 business days.