- Find a Doctor

-

For Parents

- Before Your Visit

- During Your Visit

- After Your Visit

- More Resources for Parents

Patient & Visitor Resources -

Services

- Locations

-

About Us

- About Childrens

- Find it Fast

- Additional Resources

Find it FastAdditional Resources - MyCHP

ALERT:

There is construction in and around UPMC Children’s Hospital that is affecting the traffic flow – please allow for extra time traveling into the hospital.

- Find a Doctor

- For Parents

-

Services

-

Frequently Searched Services

- Asthma Center

- Brain Care Institute (Neurology & Neurosurgery)

- Cancer

- UPMC Children's Express Care

- Ear, Nose, & Throat (ENT)

- Emergency Medicine

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Heart Institute

- Genetic & Genomic Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Nephrology

- Newborn Medicine

- Primary Care

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Surgery

- Transplant Programs

- See All Services

-

Frequently Searched Services

- Locations

- About Us

- MyCHP

- I Want To

- More Links

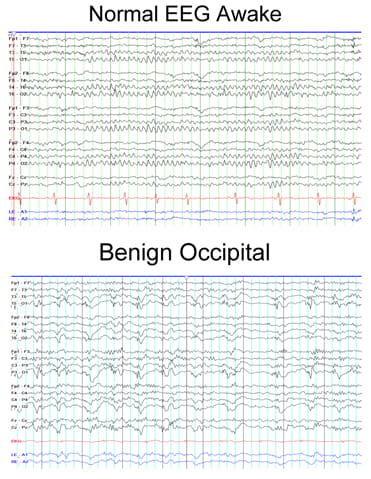

Benign occipital epilepsy, also known as benign focal epilepsy with occipital paroxysms, is a hereditary type of epilepsy that represents about 3 percent of all childhood epilepsy cases. There is a somewhat higher incidence in girls than in boys. This type of epilepsy can be grouped into two categories, depending on the age of the child when seizures begin.

Benign occipital epilepsy, also known as benign focal epilepsy with occipital paroxysms, is a hereditary type of epilepsy that represents about 3 percent of all childhood epilepsy cases. There is a somewhat higher incidence in girls than in boys. This type of epilepsy can be grouped into two categories, depending on the age of the child when seizures begin.